Introducing the Hearthstone Project

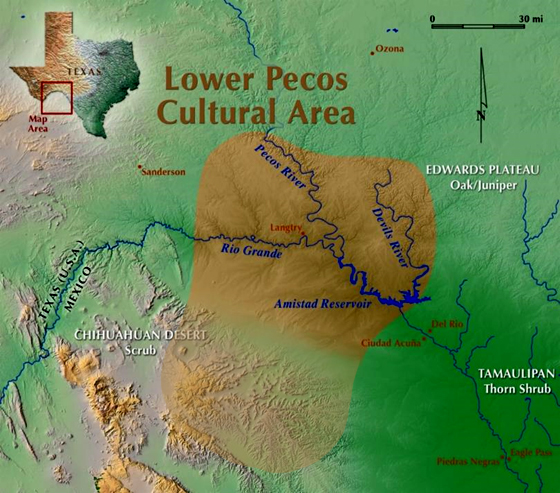

The Hearthstone Project is a collaboration between Texas State University and Shumla Archaeological Research and Education Center. The project is anchored in both science and the humanities, combining two research and preservation efforts, both partially funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Science Foundation. It is a comprehensive study and documentation of prehistoric art in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands of Texas and adjacent Mexico.

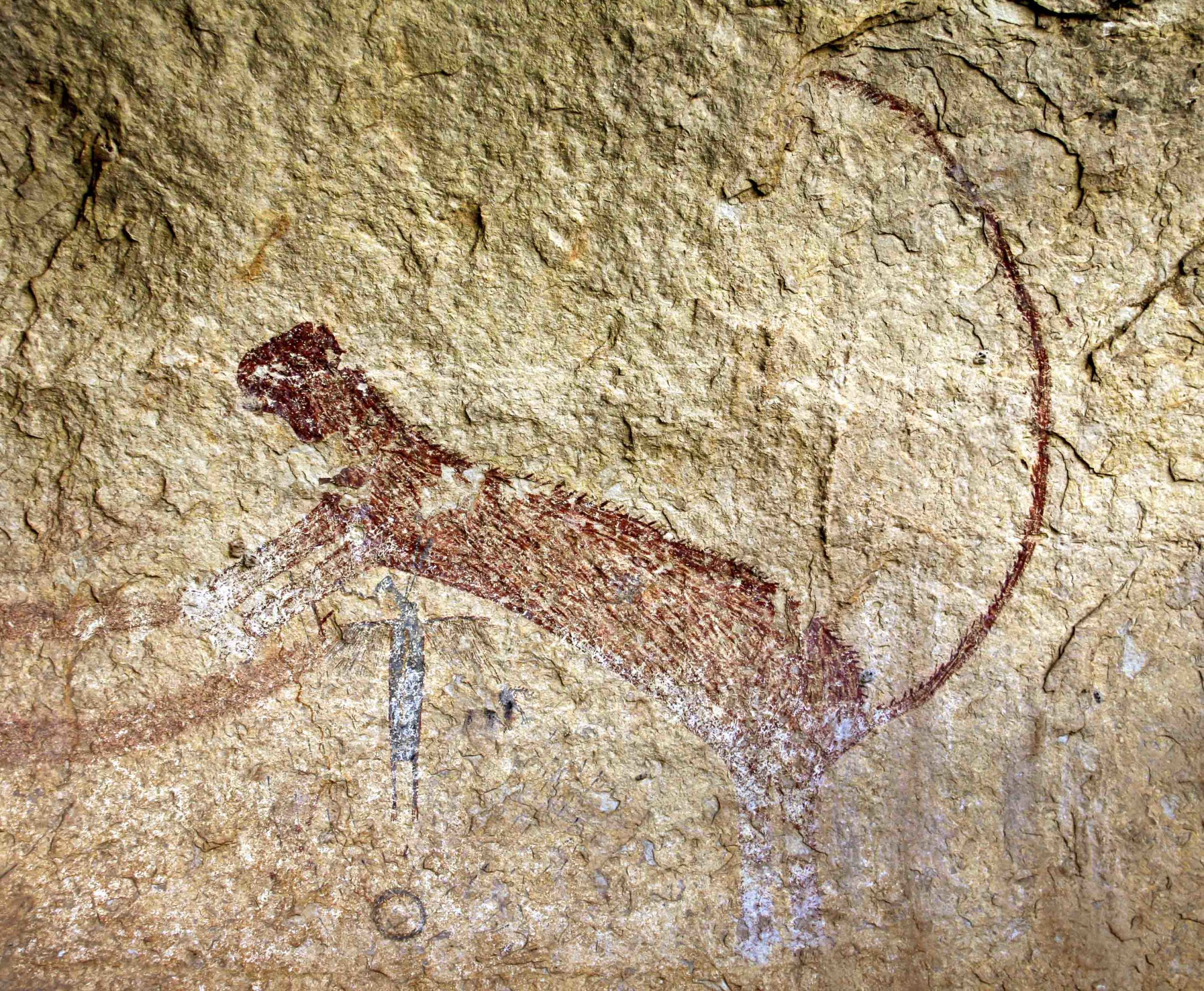

Near the confluence of the Rio Grande and Pecos Rivers, archaeologists have identified over 300 rock art sites. Our research will focus on the oldest and most widespread type in the region, Pecos River style pictographs, created with multi-colored paints in many shades of red, yellow, black, and white as early as 3,000 years ago.

The Hearthstone Project springs from a recently completed rock art recording effort, the Alexandria Project, conducted by the Shumla Archaeological Research and Education Center. The Alexandria Project recently gathered baseline data for 235 rock art sites in the region. Researchers at Shumla and Texas State University used the data gathered by the Alexandria Project to write research proposals to the National Endowment for the Humanities and to the National Science Foundation. Thus, the Hearthstone Project represents the first fruits of the data gathered by the Alexandria Project.

The murals are complex, populated with individual human-like (anthropomorphic) and animal-like (zoomorphic) figures. The artists, from small hunter-gatherer groups, painted these symbolic icons into an interwoven tapestry, arranging them in complex spatial relationships with each other. They interact, facing toward each other, flying over and under other beings, or facing straight forward engaging the viewer. They are not static; they perform. They speak and act out stories that convey the collective world view of the society that produced them. They are laden with information about the painters and their people.

Our goal is to digitally preserve the art and study the information it contains. We will unlock its stories, discover the techniques used by the ancient artists, and detail the complexity of a belief system illustrated in the murals by groups of hunter-gatherers. We will study the temporal history of the art: when it began, fluoresced, and ended. We will connect the trajectory of Pecos River style art to the environmental and cultural conditions that triggered and ended its production.

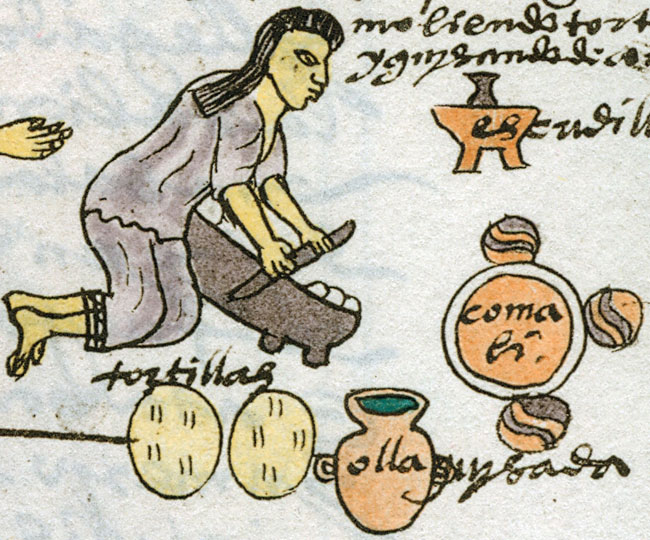

The Hearthstone Project is named for the fire hearth, a focus of domestic life and food preparation in Native American culture. Centered in the household and a part of daily activities, the fireplace was not only functional, but also powerful and symbolic at many levels. In Mesoamerican households, the hearth was made with three stones supporting a clay griddle or comal, on which food was cooked. Three stones or pillars comprise the most stable arrangement of any support system. Imbued with sacred powers, the hearthstones supported not just the comal but also centered the universe. Inside the hearthstones burned a fire, a powerful, purifying, and transformational agent. The hearth fire represented the center of the universe and the source of all knowledge and wisdom. It was the portal to the upper, middle, and underworld, and the intersection of past, present and future.

Analysis of the Pecos River style art will serve as our portal to the world view of the artists that produced the ancient murals. Like the comal, our research effort is supported by three pillars of inquiry: archaeological science, formal art analysis, and Indigenous wisdom (consultation). Pecos River style art is a rich source of knowledge that requires diverse approaches to adequately document, deconstruct, decode, and trace its history. Our research will address the issue from three directions, not just preserving the art in detail, but also providing a balanced assessment of the art and demonstrating its value as a rich source of information.

The artists, and likely their companions and relatives, carried these images inside themselves, during the day when hunting or building fires for earth ovens, and during the night when they slept. There is nothing trivial about these paintings. They represent the beliefs, thoughts, and prayers of the people – the hunter-gatherer society – that produced them. Their message lives on in shared Native American beliefs today, demonstrating the tenacity of myth. As a representation of belief and faith, they also are a physical manifestation of our shared humanity. Pictographs are an integral part of Native American heritage. Often dismissed as either incomprehensible or a commodity to sell at auction, they warrant preservation through documentation and study because they are a part of our past. And, as it turns out, they speak volumes to our present condition.

What’s Next? The next blog entry will describe the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Science Foundation research designs, and how the two approaches complement each other under the umbrella of the Hearthstone Project. Stay tuned and follow along on our journey to unlock the many stories of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands of Southwest Texas!

Further Reading:

Headrick, Annabeth. 2001. Merging Myth and Politics: The Three Temple Complex at Teotihuacan. In Landscape and Power in Ancient Mesoamerica. Edited by Rex Koontz, Kathryn Reese-Taylor, and Annabeth Headrick. Pages 169-188. Westview Press. (Reissued by Routledge: Taylor and Francis Group in 2018).

Headrick, Annabeth. 2007. The Teotihuacan Trinity: The Sociopolitical Structure of an Ancient Mesoamerican City. The University of Texas Press. Pages 110-118.

Read, Kay, and Jason Gonzales. 2002. Mesoamerican Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs of Mexico and Central America. Oxford University Press. Pages 20-24.

Taube, Karl 1998 The Jade Hearth: Centrality, Rulership, and the Classic Maya Temple. In Function and Meaning in Classic Maya Architecture. Ed. By Stephen D. Houston. Dunbarton Oaks. Pages 429-478.