Painted Canyon

“We find the country to consist of a vast table elevation cut up by some great convulsion of old time into numerous ravines or canyons.” William Whiting, Journal of William Chase Whiting, 1849.

During the first two weeks in May, Shumla and Texas State University conducted field research for the Hearthstone Project. We reserved the first week for Jackrabbit and Jaguar shelters in Painted Canyon, a tributary of the Pecos River.

Painted Canyon, Jackrabbit and Jaguar Shelters

Painted Canyon houses two spectacular rock art sites, Jackrabbit and Jaguar shelters. The mural in Jaguar shelter is the oldest mural we have yet radiocarbon dated in the region. It may contain the oldest securely dated pictographs in North America. We are conducting additional research as part of the field work described in this blog to confirm our findings.

Our objective: In Painted Canyon, our goal was to collect paint-layering data from figures that we are radiocarbon dating. When we find several figures connected by interwoven paint layers, we know that they were painted at the same time. If we date one spot in those paint layers, we have obtained a date for the entire interwoven area.

Getting there: We knew the week would be difficult. It can be hard to get where you want to go in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. The region is unusual in that most of our destinations are so close in linear miles, yet so distant in the time and effort it takes to access them. It is rough. How rough? The best descriptions come from the journals of early explorers.

In 1590, Gaspar Castaño de Sosa described his difficulties crossing the region “. . . All were in despair on account of the great amount of rock encountered on the trip in search of the Rio Salado (Pecos River)—which we were seeking. There were used up in these mountains 25 dozen horseshoes, because it was not possible to travel by any other route. Many horses used up their shoes in two or three days, an unbelievable thing.”

“They (a scouting party) found the Rio Salado (Pecos River) . . . though they could not enter into it on account of the many sharp rocks (pena tajada) and ravines.” (Shroeder and Matson 1965:41,49.)

In 1849, William Whiting echoed Castaño de Sosa’s lament: “The canyon by which we left the Pecos, bearing off to the southeast, was rough and difficult. Chapparal (here very thick), cactus, and the various stony gullies made the march for a few miles very severe . . .”

These two descriptions are separated by over 250 years, but the rocks had not changed much, nor have they changed much today. Whiting was better at describing topography; there are no mountains in the region, it is the edge of a plateau lacerated by steep, narrow, boulder-filled canyons.

Although it is only a few linear miles north of Comstock and US Highway 90, it takes about 1 ½ hours to drive 28 miles to get to Painted Canyon. But the drive only gets you to the campground, not the two rockshelters that were the subject of our study.

Logistical challenges for Painted Canyon were a bit daunting, but Tim, Audrey, and Diana rose to the occasion. The camping area has no water or electricity, and we needed both. We had to bring enough food and water to last several days, and a generator for a charging station. Most of our equipment runs on batteries.

Figure 1. We set up camp near the edge of the Pecos River canyon. This is a panorama of the campground on the east side of the Pecos River. Tents and trucks in background, charging station in the center, electrical extension cord running from the generator to table in the foreground.

Figure 2. Our field charging station with generator in the distance.

The team worked hard to get our equipment to the rock art sites. From the campground we first had to climb into the Pecos River canyon, ford the Pecos River with equipment, and then boulder-hop up Painted Canyon for 3 hours to get to Jackrabbit shelter. By boulder hopping, I mean climbing, balancing, crawling, and scooting across the boulder strewn canyon floor. Some crew members were carrying equipment weighing 40 pounds or more.

Figure 3. Descent into the Pecos River canyon.

Figure 4. Karen Steelman demonstrating the butt-slide method of descent. The narrator adopted a similar approach. The sharp rocks (pena tejada) made short work of our hiking pants. Many of us are in the market for new ones.

Figure 5. Wading across a crystal-clear river. It’s easier to do if you are not carrying cameras and electronics.

Figure 6. The water rose to backpack level on the other side of the Pecos.

Figure 7. Here the team is picking their way up Painted Canyon. Diana Rolón carries a ladder and gives directions to Carolyn Boyd. Tim Murphy, in the background, looks on. Dering is trying to judge his next step.

Figure 8. Audrey Lindsay demonstrating rock-climbing skills with a loaded backpack in Painted Canyon.

Working at Jackrabbit: After a three-hour hike, we reached Jackrabbit Shelter. The climb into the shelter was, relatively speaking, easy, but some of the images were difficult to access. Our first day there we were running two microscopy teams.

Figure 9. Many images at Jackrabbit were high on the shelter wall, or on the ceiling. Here Tim Murphy and Diana Rolón perform a balancing act while working on the microscope and tablet; Seamus Anderson keeps the photo records.

Figure 10. During our first day in Jackrabbit shelter, we worked in two microscopy teams. Tim Murphy and Diana Rolón in the foreground, Carolyn Boyd and Phil Dering in the background. Kelly Timmons did much of the record keeping, but in this photo Karen Steelman is the recorder.

Figure 11. (L to R) Seamus Anderson, Tim Murphy, Diana Rolón on the stepladder, and Audrey Lindsay. Did I mention mosquitoes? Clouds of them. Tim and Audrey are not scratching their chins in puzzlement.

Figure 12. The namesake figure of Jackrabbit shelter is a rabbit-like head (upper right) mounted on what appears to be a spinal column, which is held by an anthropomorph. The red, horizontal bar is part of a feathered, fish-like figure that stretches for a few meters across the mural.

Figure 13. A closeup of the jackrabbit head.

What have we learned so far at Jackrabbit? All figures included in the radiocarbon study were woven together. This means that we will have direct dates on a planned composition, and that we know when most of this mural was painted. The Jackrabbit pictograph is yet another example of a carefully planned and executed mural that followed rules of paint color application: black first, then red, then yellow, and then white.

We are radiocarbon dating five figures at this site: the head of a large, feathered fish-like figure, the torso of the rabbit-ear anthropomorph painted across the fish-figure, a black anthropomorph, a red rectangular design inside the body of another anthropomorph, and the body of an anthropomorph with red feet. Preliminary data suggests that these were all painted about 4700 years ago.

Camp life:

I wrote these two entries in my field journal (May 3, 2022):

“We arrive at 6:30PM and set up camp. We complete the setup in the dark. We needed an extra hour of daylight to set up the camp and stage the gear. After dark, the southeast wind dies, and the flying insects are so thick we cannot stay outside our tents. We move into our tents. It is a sultry, still night—temperature inside the tent is 85° and the humidity is over 90%. After midnight, a slight breeze carries cooler air into the tent.”

“Awake and up by 6AM. Early morning temps around 76-78°, humid, wind SE <10mph. We eat breakfast in a cloud of insects both large and small and prepare to leave for the site in the dark. As the sky lightens, we leave camp around 7:10.”

Anyone who has spent time in the region knows that this weather is more typical of June or July. Worse, we arrived two weeks after the first decent rainfall after a dry winter. Semi-arid regions tend to burst with life after such an event, and we were there to experience it.

Figure 14. Although Carolyn and I had a good setup, we were moving slower than the younger members of the team. It had been a few years since we slept on the ground.

Figure 15. The ever-adaptable Carolyn Boyd demonstrates how to drink coffee in a cloud of insects. Some of us just accepted the extra protein.

Jaguar Shelter:

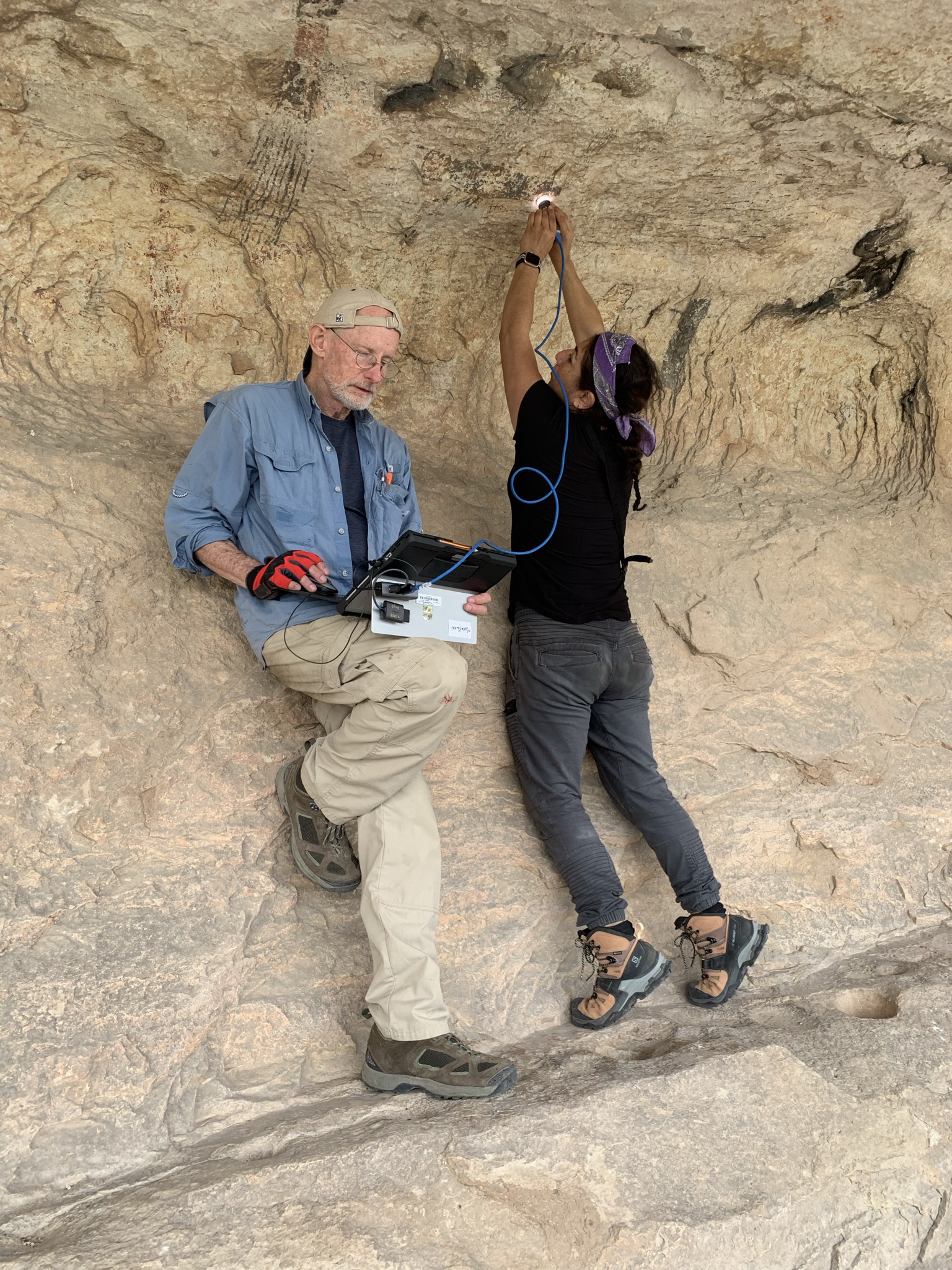

Most of the team spent more time in Jaguar shelter. Jaguar shelter is one of the oldest pictograph sites in the region. As in Jackrabbit, we wanted to investigate paint stratigraphy around figures which we are radiocarbon dating. The team conducted much of the microscopy while standing on a narrow shelf a few feet above the floor of the shelter.

Figure 16. Karen pauses to smile, and maybe gather her wits, during a morning climb through Painted Canyon to Jaguar.

Figure 17. At Jaguar shelter, Drs. Carolyn Boyd and Diana Rolón choose a microscopy site based on the annotated site maps Diana prepared. Seamus Anderson observes.

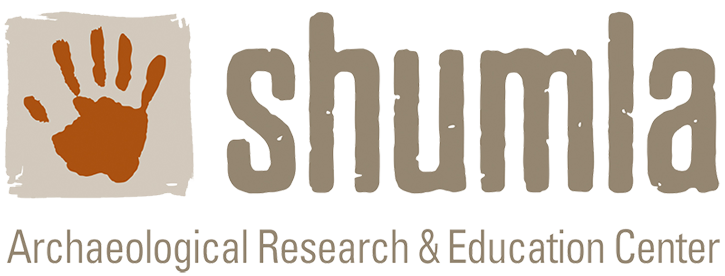

Figures 18. Lunch and a siesta. Karen Steelman, Phil Dering, and Carolyn Boyd taking a break.

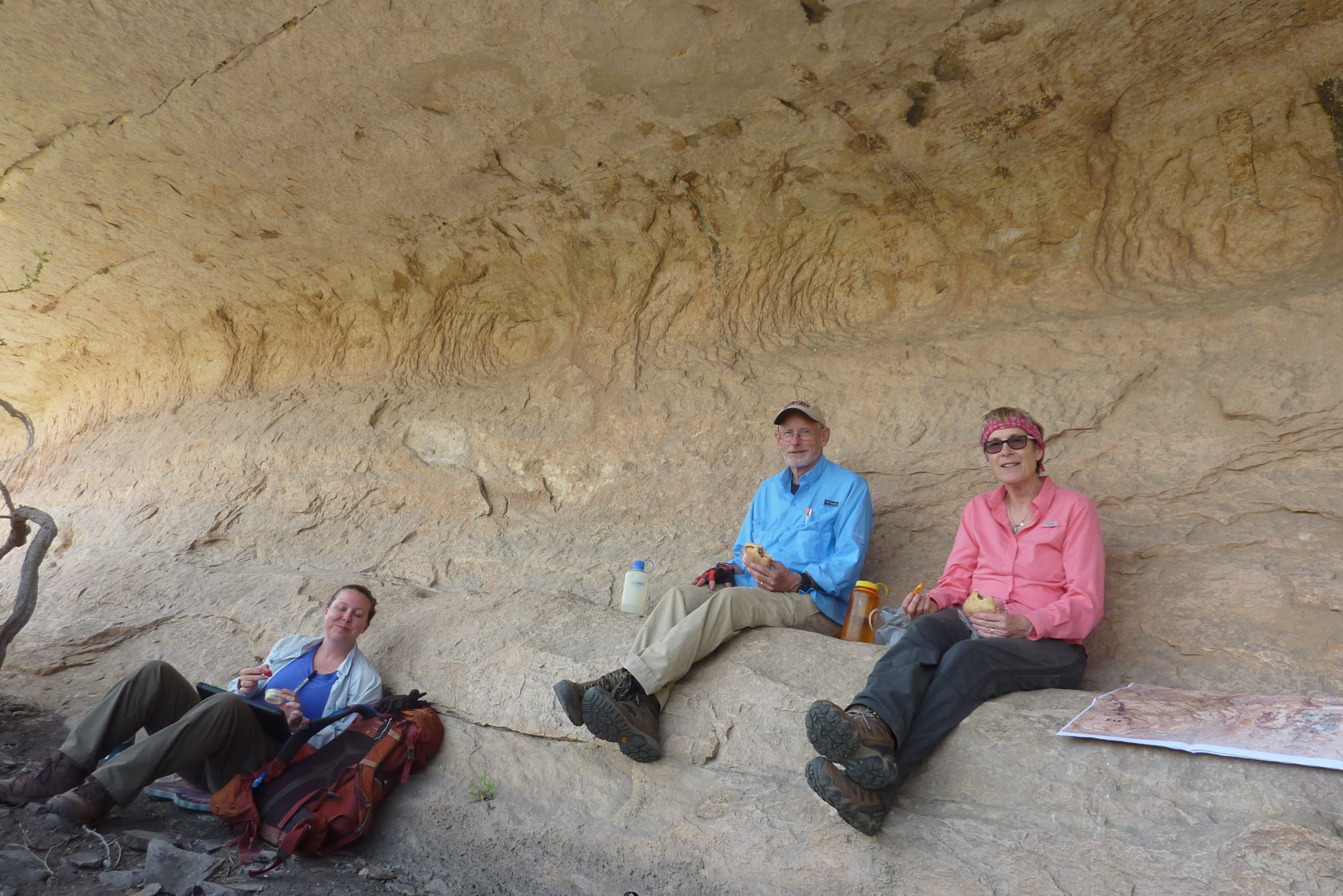

Figures 19 and 20. Carolyn proves that you can sleep on an extension ladder. Phil and Carolyn on the microscope and tablet. Teamwork for three decades!

Figure 21. Tim Murphy mugging it up with the mugboard. This was the only piece of equipment he carried that weighed less than 30 pounds. Seamus Anderson on the camera.

Figures 22 and 23. Diana and Phil working on the ledge. Diana on tiptoes on a ledge above the shelter floor; yes, it was painful.

Figure 24. Black circles infilled with red, inside the torso of a yellow anthropomorph: The visual effect resembles a jaguar pelt.

What have we learned so far at Jaguar?

- A red dry-applied line weaves over the black and under the yellow paint layers connecting almost every figure on the panel. Because the figures are interwoven, we know that they were painted at the same time. You cannot paint underneath paint.

- The jaguar anthropomorph was painted by a rule that governs the order of paint color application. The black circles were painted first, then red, then yellow.

- A closer examination of remnant patches of paint convinced us that the mural once covered the ceiling.

Figure 25. Kelly Timmons and Carolyn Boyd pause for a water break on a 95° afternoon in early May. Notice the step ladder strapped to Kelly’s full backpack. She volunteered for this, not knowing exactly what she was getting into. She recorded much of our data and lugged equipment into the canyon. We hope she comes back, but we will forgive her if she doesn’t!

Figure 26. (L-R) Drs. Karen Steelman, Diana Rolon, Phil Dering, and Carolyn Boyd.

Our research is just beginning. Targeting specific locations within the two shelters, we collected microscope images at 110 locations. Over the next several weeks, a team of researchers will examine those images to make final determinations of paint layers. Karen Steelman will prepare samples for radiocarbon dating, and Diana Rolon and Carolyn Boyd, with the help of graduate students, will examine the microscopy images. Phil Dering will help prepare the Harris Matrix for the two panels.

Stay tuned as we analyze our data and publish these exciting new results in the next months ahead! We are learning so much about the people who created these amazing murals!