Ethnographic Fieldwork in San Andrés Cohamiata, Mexico (Part One)

When the experience is as interesting as the data we collect

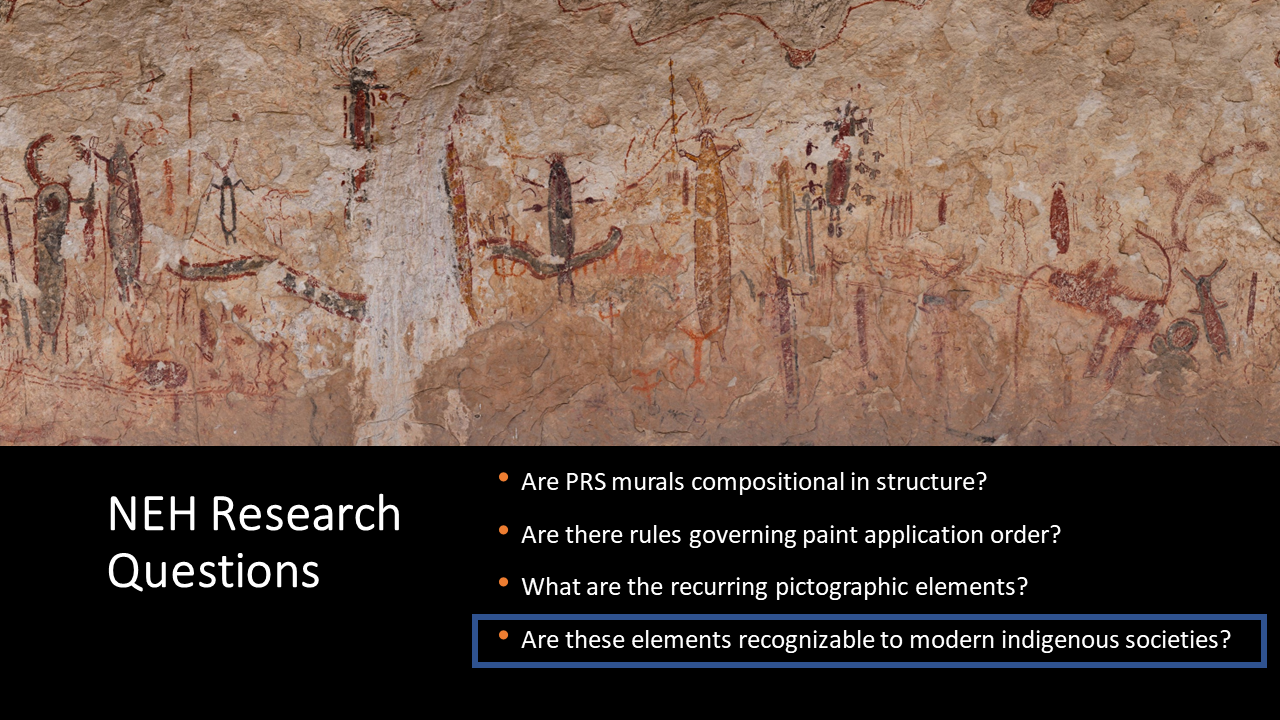

The Encounter That Brought Us to Mexico: Matsua At the White Shaman Site

Thirteen years ago, Matsua, a Huichol shaman, traveled to the Lower Pecos region to the White Shaman mural and to meet Carolyn. This was an unprecedented opportunity for Carolyn was eager to find out what he thought about the mural. Did the paintings still carry meaning to Indigenous cultures today? When Carolyn brought him to the White Shaman site, Matsua stood in front of a Pecos River Style mural and told her that the images on the canyon wall were “. . . my grandfather’s, grandfather’s, grandfathers. They are all here. All my grandfathers, all my ancestors, they are all here.” Directing his attention to the paintings, Matsua spoke affectionately and reverently as he conversed with his kin, the ancestral gods from primordial times.

Figure 1: Matsua and Carolyn at the White Shaman Site, 2010. (Photo credit: Robin Matthews)

Although the canyonlands of the Lower Pecos are far from his home in Jalisco, Mexico, the site inspired an emotional and celebratory reunion with his ancestors. He read the mural, which is over 2,000 years-old, as if it had been painted yesterday. Even more intriguing, his reading of the mural paralleled Carolyn’s interpretation, which she later published in her book about the White Shaman Mural. Matsua had never visited the site and was unaware of Boyd’s analysis of the paintings, yet he was able to identify what he saw as deities and symbols that he related from Huichol cosmology. After the shaman’s visit, Carolyn thought, “Why not take the art to other shamans? Why not bring renderings of Lower Pecos art to Mexico, and see if they can read the murals like Matsua read them?”

Figure 2: Dream Realized: The Hearthstone Project

After thirteen years, she was able to realize this dream thanks to a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). In January, Carolyn and Phil traveled to Mexico to conduct the ethnographic component of the NEH project, “Origins and Tenacity of Myth, Ritual, and Cosmology in Archaic Period Rock Art of Southwest Texas and Northern Mexico”.

Our plan was to show shamans and artists Carolyn’s digital renderings of Halo Shelter, Fate Bell, Panther Cave, and the White Shaman, and record their reactions in a series of interviews. For this purpose, we completed several months of fieldwork studying paint stratigraphy at these Pecos River style sites. This work is described in the four previous installments of the Hearthstone blog. Carolyn used the data to draw scale renderings of four Pecos River style murals: Panther Cave, Halo Shelter, Fate Bell (downstream end), and Panther Cave. She printed the renderings onto scrolls up to 3 meters-long. We took these scrolls to Huichol elders living in the San Andrés Cohamiata community in Jalisco, Mexico.

Figure 4: Jim Bauml

Figure 5: Stacy Schaefer (photo credit: Jim Bauml)

Stacy Schaefer, ethnographer, Jim Bauml, ethnobotanist, who have over 40 years’ experience in the region, were our collaborators, guides, and translators. Stacy is an expert weaver and author of many books and articles on the Huichol, including To Think with a Good Heart and Huichol Women, Weavers, and Shamans. Jim is an ethnobotanist and an authority on Huichol plant use, especially the domesticated Mexican marigold, Tagetes erecta. They have longstanding ties with families in San Andrés Cohamiata, the a major ceremonial center on the western side of Huichol territory.

Stacy and Jim were old hands, having traveled into the area many times over 40 years. However, Carolyn and Phil could only imagine what to expect. We knew that our priority, our goal, was to conduct and record interviews. The interviews comprised our data, but we had to overcome several obstacles to get to the point where we could conduct the interviews.

What follows is a brief account of this journey.

Travel to Puerto Vallarta was easy for Carolyn and Phil, a nonstop flight from Austin in just over two hours. We met Jim and Stacy at the airport and took private transport north to San Francisco (also known as San Pancho). Our intent was to discuss data collection strategies and connect with some contacts before entering an area with limited communications. It was also time to get to know each other better; Jim and Stacy were taking a chance by bringing us into the Huichol community. They had developed friendships with several families that spanned three generations and involved deep family commitments. They also wanted to ensure that we (Phil and Carolyn) were acclimated to the rhythm and culture of life in Mexico. Surprisingly, we all discovered that San Pancho with its New Age vibe felt more like southern California than Mexico.

Figure 6: The team at Yasmina’s vegetarian restaurant in San Pancho. Cilantro shots, not tequila shots, served here.

We traveled from San Pancho to Tepic, Nayarit, the state capital. Our cab to the bus station in a nearby town quit running after 30 minutes or so. Fortunately, we were able to hail a passing bus that took us all the way to Tepic. It was far more comfortable than the cab. We found Tepic to be a quieter, traditional city with some very good restaurants. Stacy and Jim had several close friends living here. They helped us secure transport into the sierra.

Figure 7: The view of the Plaza de Armas (left) from our hotel in Tepic, the capital of Nayarit. The Immaculate Conception Cathedral (right) was closed; one of the towers is being repaired.

Barriers to Access

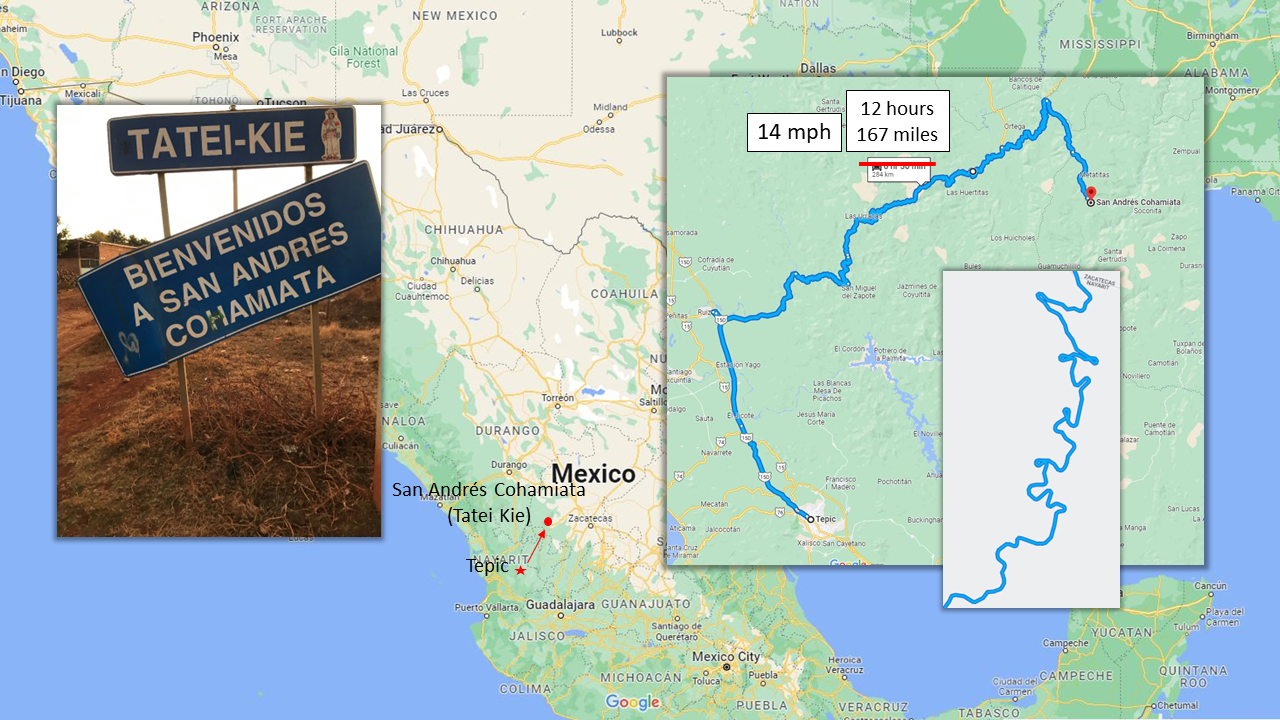

In Tepic, we faced several challenges. The first challenge, and the most daunting, was to find a way into the mountainous region and the community of San Andrés Cohamiata. In Waxárika, the Huichol language, it is called Tatei-Kie. Despite limitations to communication into the region, Stacy and Jim had been able to contact friends and family in San Andrés, and they were expecting us to arrive on a particular day. But we were having difficulty finding a way in.

Figure 8: The squiggly path suggests the nature of the road to San Andrés Cohamiata in two dimensions. (Google Maps image). The 3-D version was even more interesting (see next image).

Figure 9: San Andrés Cohamiata (red pin) is located on a small mesa surrounded by a seemingly endless series of deep chasms. The deepest part of the canyon in the upper right of the image, 8km to the east, is over 4000 feet below the level of the mesa. (Google Earth image).

One would think that in the 21st century most areas would be easily accessible, especially since Mexico has a robust mass transportation system. It turned out that not many buses, or other forms of transport, were running to San Andrés Cohamiata. A weekly DC-3 (C-47) flight once took passengers from Tepic, to the airstrip at San Andrés, at 6,400 feet elevation. But in a reaction to drug cartel activity, in recent years the government had shut down the airstrip and dug trenches across it, rendering it inoperable.

Figure 10: Carolyn and Daisy walking alongside the airstrip on the mesa in San Andrés. One of many trenches dug across the airstrip by the government is visible in the foreground.

We learned this after trying to find a ride in a small aircraft. Due to the same problem, along with the poor condition of the road, we could not find a driver to take us in a truck or SUV to San Andrés. We discovered that within the last few months, competing cartels were putting up temporary checkpoints in the sierras between Tepic and San Andrés, along the borders of Nayarit, Zacatecas, and Jalisco. These factors were discouraging casual travel and limiting public transport into the region.

Figure 11: In Tepic: Jim, Carolyn, Lily, and Stacy in front of one of the bus stations on Lily’s list. An internet search did not find our bus. Lily took us to each bus station so we could check bus routes in person.

Stacy teamed up with a long-standing friend, Lily Hernandez, who launched a search for a bus ride into the sierra. She came up with a list of five small bus companies that might take us all the way from Tepic to San Andrés. After driving to each small bus company, a process that lasted several hours, their persistence paid off with the last station on the list.

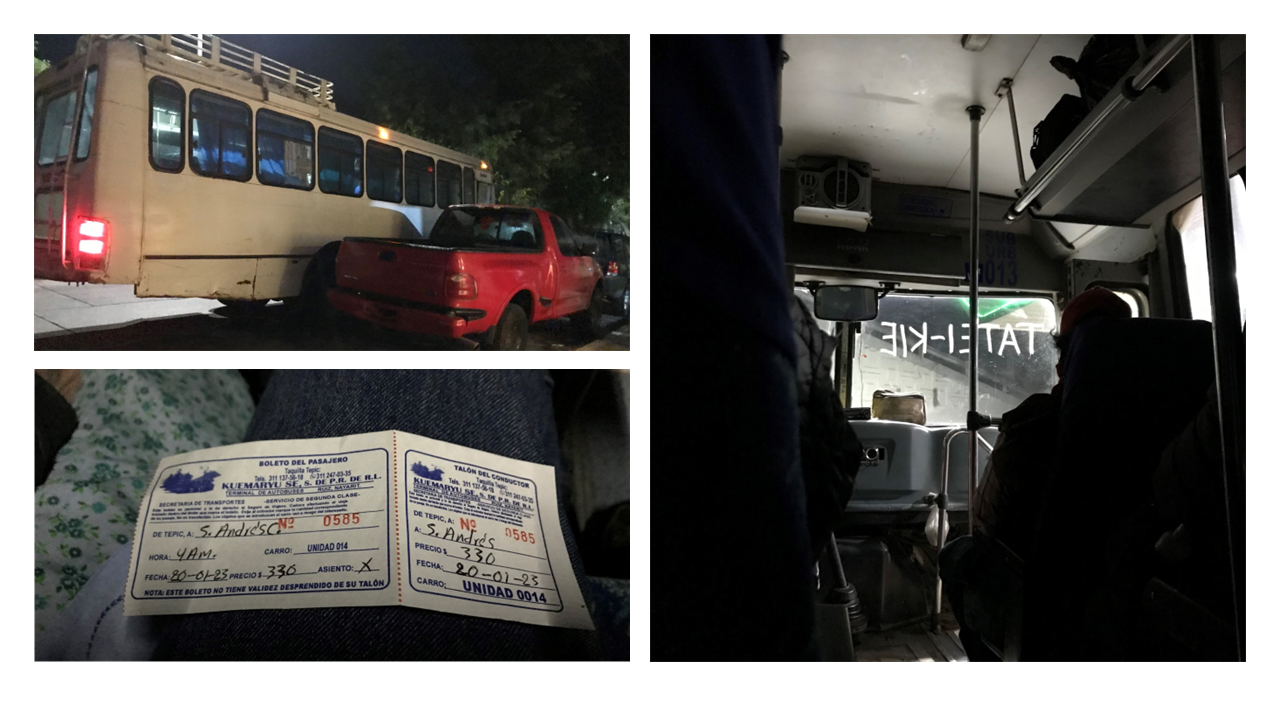

The hitch? It left at 4AM and arrived in San Andrés at 4PM, only on Wednesdays and Saturdays. As you can see in the image, the facilities were basic. We found the tiny bus station on a Friday, bought our tickets, and prepared to wake up around 2AM the next morning, January 21, to make final preparations for the trip.

Figure 12: Lily, Jim, and Stacy are asking for bus schedule information from a man behind a desk in a small dark room in Tepic. The schedule, painted on the wall above the number “18”, was simple: depart at 4AM on Wednesdays and Saturdays, return at 4AM on Thursdays and Sundays. Arrival time? 12-14 hours later.

Figure 13: A bus ticket to San Andrés Cohamiata. MX$330, US$17 for a 164-mile (265km), 12-hour ride. The Huichol name for their community does not appear on the ticket. Our chariot to San Andrés was double-parked in front of the bus station. Traffic was not a problem at 4AM. The Huichol name for San Andres, , was painted in white shoe polish on the inside of the windshield.

We arrived at the bus station around 4:00 AM, early enough to secure good seats near the front. Freight and suitcases/backpacks were transported in the back and later in the trip, extra riders were seated on the roof. After the passengers boarded the bus, the conductor wrote the Huichol name for our destination in white shoe polish on the inside of the windscreen, starting to the right and moving leftward. He turned to the passengers, bowed, and received a round of applause. Then, around 4:40 AM, we left for Tatei-Kie.

The bus was an old warrior. Some of the body and suspension parts were secured with wire and rope, a common repair strategy in the sierras. The driver worked closely with the conductor, who watched the road and called out obstacles such as deep potholes and fallen boulders large and small, not to mention the unguarded, precipitous drop-offs around tight corners. As part of the meal plan, every rider got a free tasty tangerine and access to reasonably priced tortas and tacos from vendors that sometimes hopped on and off the bus while it was moving.

We were also provided with several rest stops: women behind the bus and men to the front. I felt safe, entertained, and well-cared for throughout the entire ride.

Working off the Grid

Once we made it into the region, we knew we had to operate our recording equipment off the grid. We brought solar panels and power banks that could operate tablets, recording devices, and charge camera batteries. Choosing the devices was difficult. The equipment had to be lightweight yet effective. Airlines put strict limits on the capacity of lithium-ion power banks, and solar panels are heavy. The equipment could not fail, so we needed some redundancy. We settled on a pair of 100wH power banks and two 20W solar panels that could be transported in two separate backpacks and coupled in a series to produce more charging power. The setup worked well.

Figure 14: Our off-the-grid recording and charging equipment had to be both portable and dependable. This setup worked well: two 100 Wh power banks and two 20W solar panels joined in a series, aided by abundant sierra sunshine in the dry season.

Figure 15: Jorge (photo credit: Stacy Schaefer)

Figure 16: Cristalina

Securing Permission to Stay and Work in the Community

At this time, there are no public accommodations in San Andrés. Outsiders who want to stay here must have a host. Using relationships built over 40 years, Stacy and Jim arranged for us to stay with Jorge and Cristalina. Stacy is Cristalina’s godmother. Following the customary treatment of house guests, the family prepared our meals with food supplies we bought at local tiendas and gave us a place to sleep. This is demanding work. We could not overstay our welcome, so we had two weeks to complete the interviews.

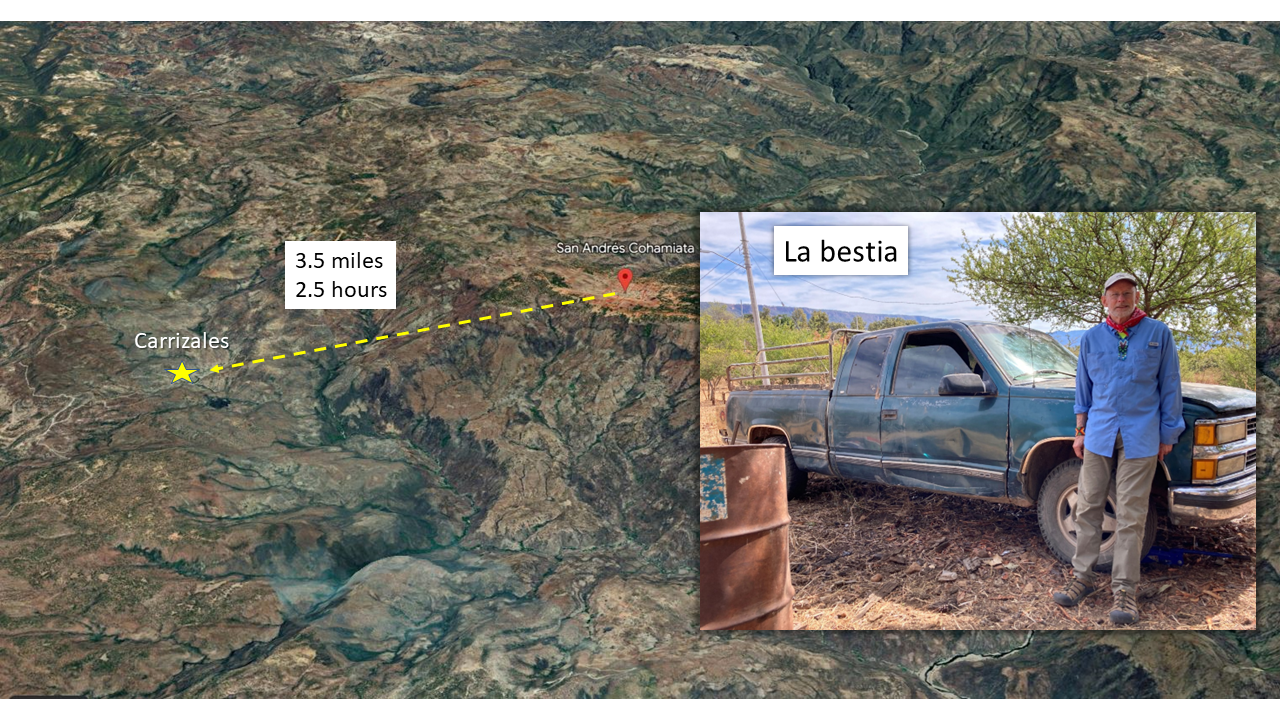

The broader community served by the traditional government in Tatei-Kie covers a large area around the town. It is divided into several smaller family farmsteads, or ranchos. Our hosts currently split their time between one rancho on the mesa at the edge of San Andrés, and another one about 3.5-4 linear miles to the west, in the barrancas near Carrizales.

Figure 17: The team walks into San Andrés to find friends and meet with the traditional governing council of to gain permission to stay. Phil trails behind with the camera.

Our host family had journeyed 2.5 hours from their rancho in the barrancas to meet us in San Andrés Cohamiata. The first night we stayed on their property at the edge of town. The next morning, we secured permission to stay in the region from the local authorities. A few hours later, Jorge drove us to the family’s ranch in the barrancas, an area referred to as “Tierras Coloradas”, located at 4,700 feet elevation.

Figure 18: A Google Earth view of the two ranchos. The barranca ranch was about 3.7 miles distant as the crow flies, from the ranch on the mesa. However, La Bestia (the truck, not Phil), could not fly. Because we had to drive around the deepest canyons, the trip took 2½ hours.

Figure 19: La Bestia is a twenty-five year old ½ ton pickup truck. It lived up to its name, delivering us safely to our host rancho. La Bestia’s gas tank was fastened to the frame with rope; I am glad I did not know this before the journey. It became obvious that Jorge is skilled at repairing everything, using anything. A couple of weeks later, I watched him replace the steering box using a few wrenches and a hammer.

The next installment, In the Barrancas, describes our first week in Huichol country, at a host rancho in the Tierras Coloradas.