To Iconography… And Beyond!

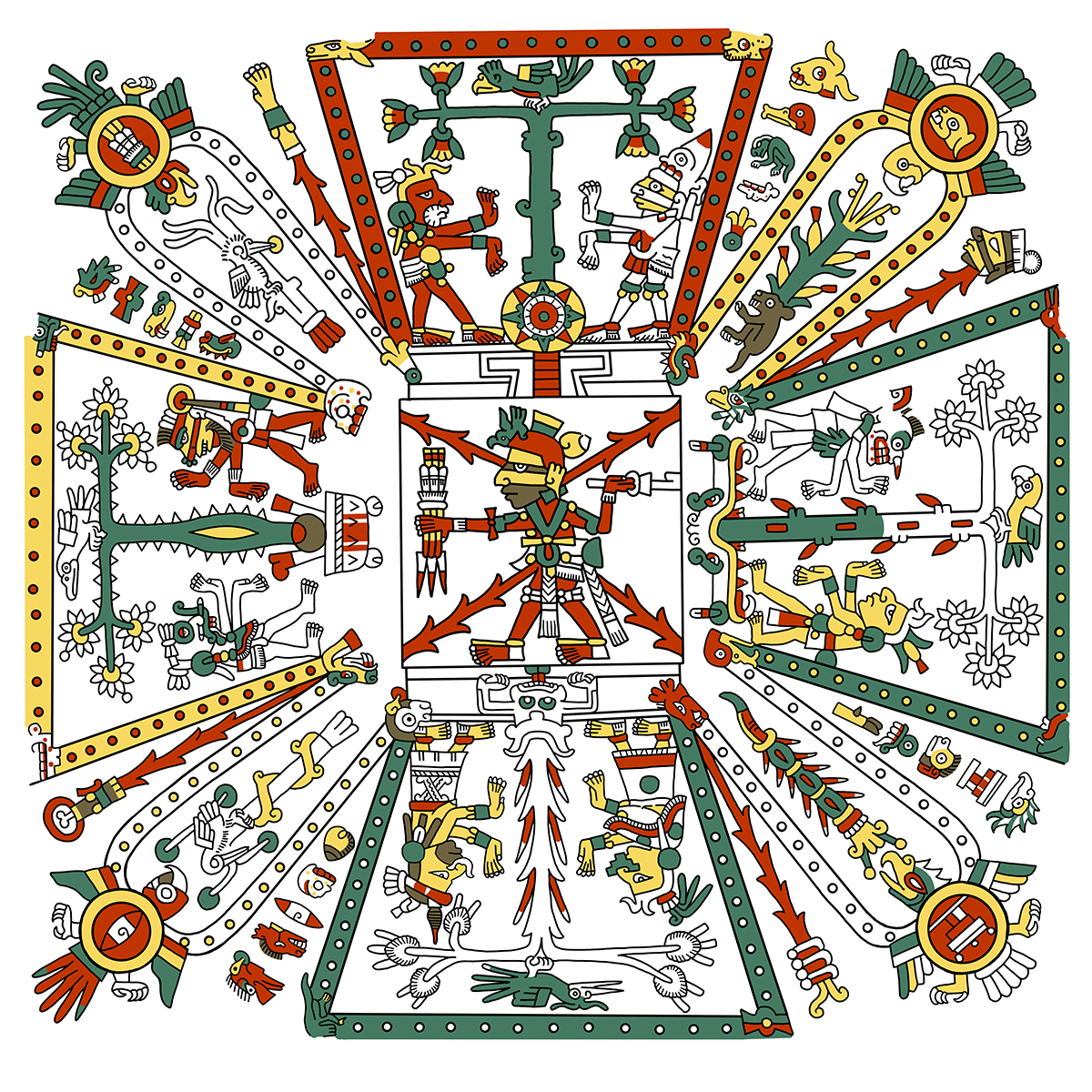

This blog post focuses on a key aspect of Shumla’s documentation methods and the Alexandria Project: iconography. Iconography includes the documentation, study, and interpretation of images and symbols. Archaeologists working across the world are studying the iconography from many cultures, including the Moche in Peru, Mississippian in the American Southeast, and the various symbols and artworks of the Egyptians. Further, as anthropologists, we take the historical and cultural context of the pictorial motifs into consideration. In other words, we think about how the iconography fit into the culture that created it.

What is Iconography?

The Lower Pecos, as you all know, hosts an amazing and diverse iconographic dataset in the form of rock art that we are just now beginning to understand. To do this, we loosely follow a multi-step approach of iconographic study called “Panofsky’s Method.” Erwin Panofsky was a renowned art historian that pushed iconographic study into the realm of what he termed iconology. Panofsky ([1939] 1972:3) defined iconology as “that branch of the history of art which concerns itself with the subject matter or meaning of works of art, as opposed to form.” For Panofsky, art carries three levels of meaning: natural, conventional, and intrinsic. Each of these levels require a progressively deeper understanding of the culture that produced the imagery.

Iconographic Analysis and Shumla

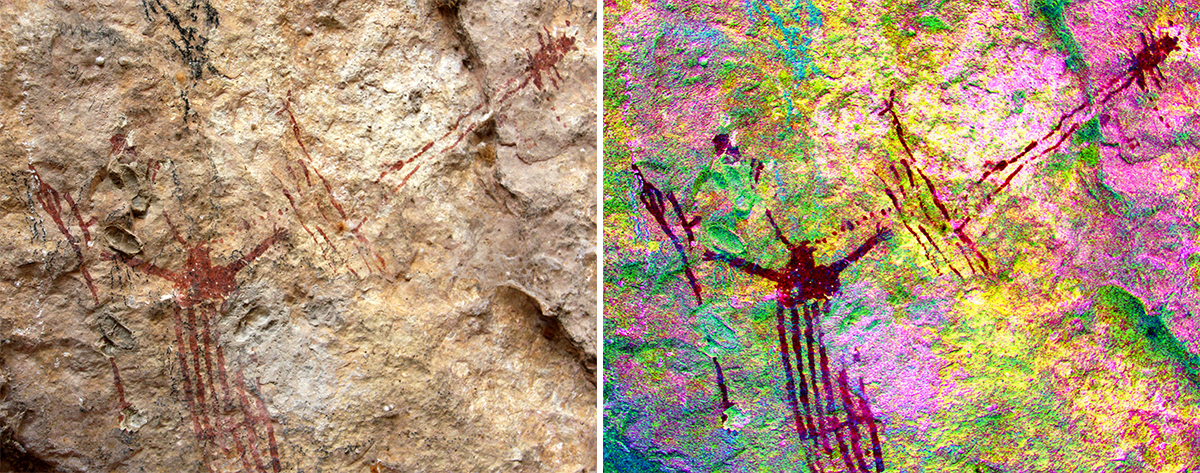

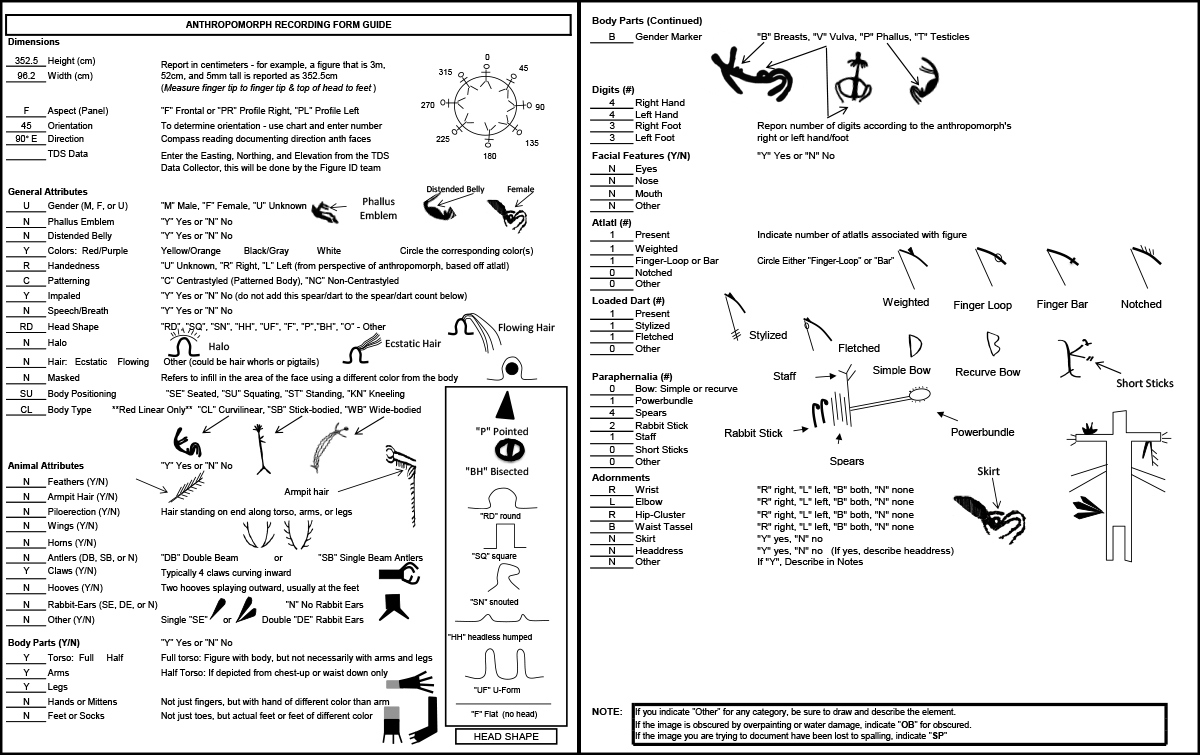

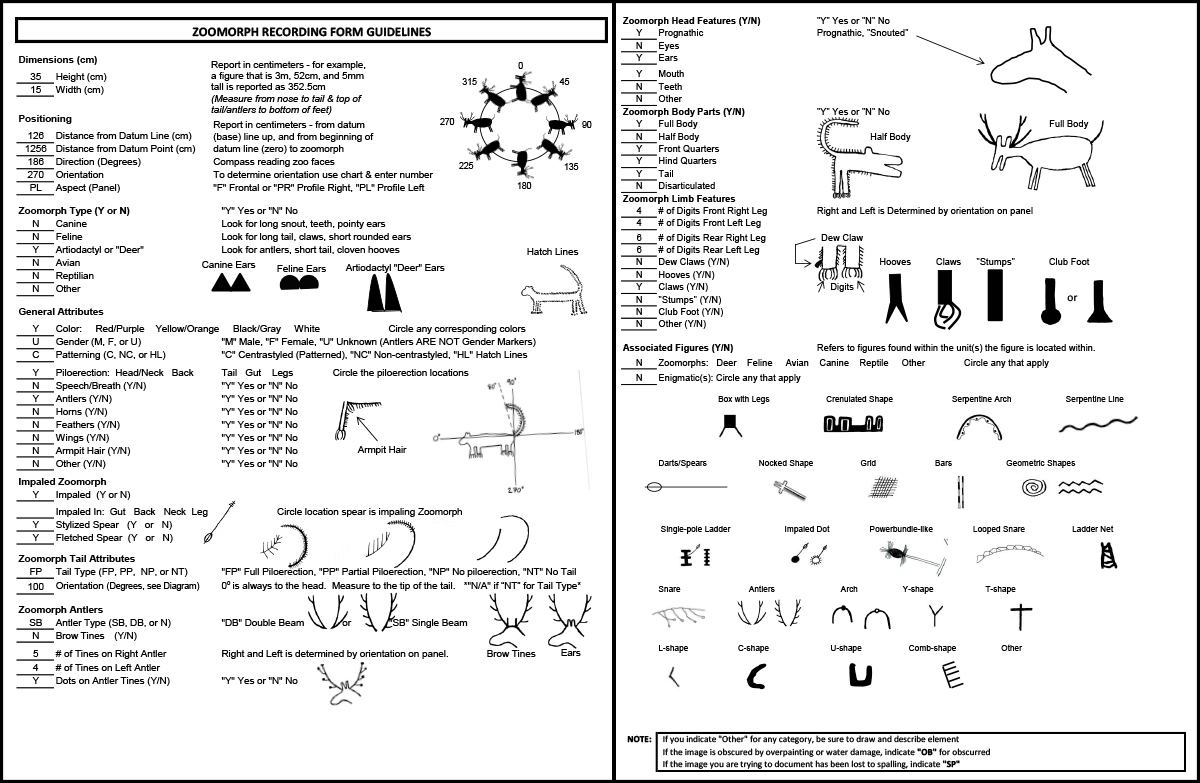

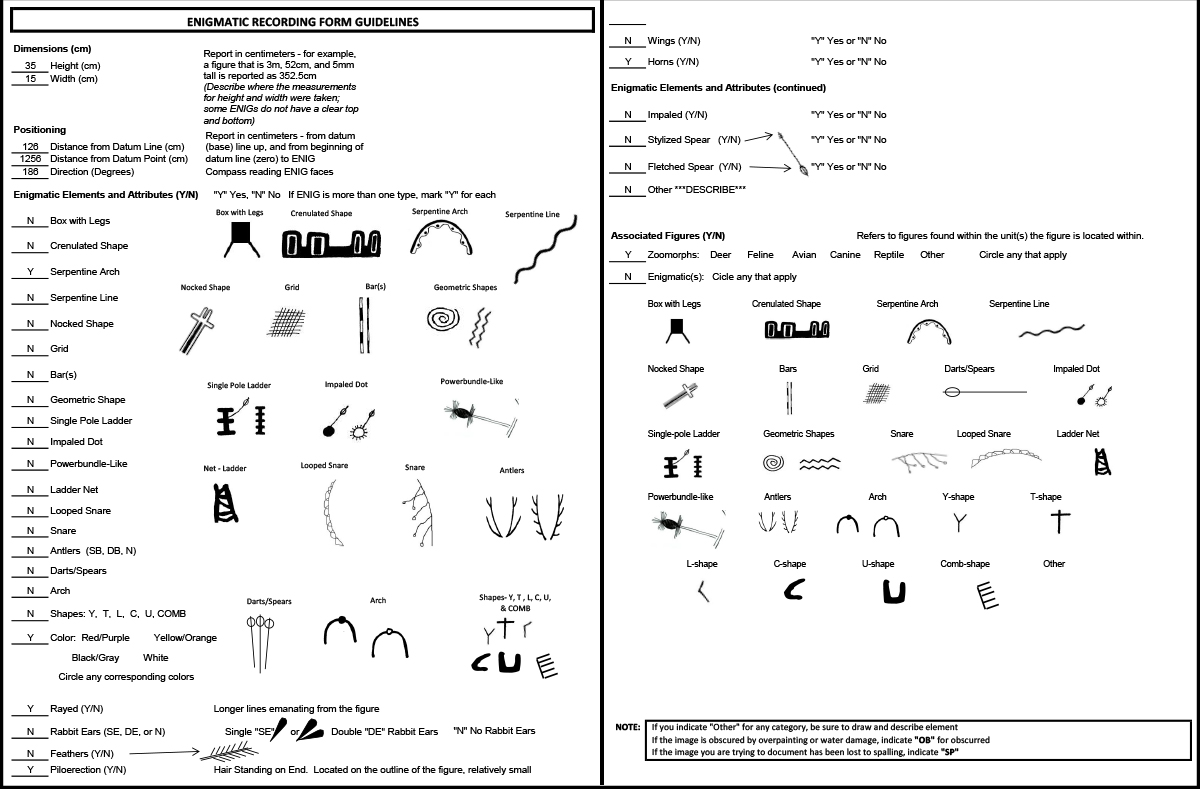

Ever since Dr. Carolyn Boyd started Shumla, we have emphasized iconographic documentation as a way to not only document the rock art, but also analyze and study the figures (see Shumla Method). The first step in this analysis was to categorize the types of figures we see in the rock art. We settled on three major categories: 1) anthropomorphs (human-like figures), 2) zoomorphs (animal-like figures), and 3) enigmatics (neither human nor animal-like figures). We then compiled a list of iconographic attributes that we record for any single figure type. We collect over 70 individual attributes for anthropomorphs, over 50 attributes for zoomorphs, and over 30 attributes for enigmatic figures.

Anthropomorph

Zoomorph

Enigmatic

Iconographic Inventory and the Alexandria Project

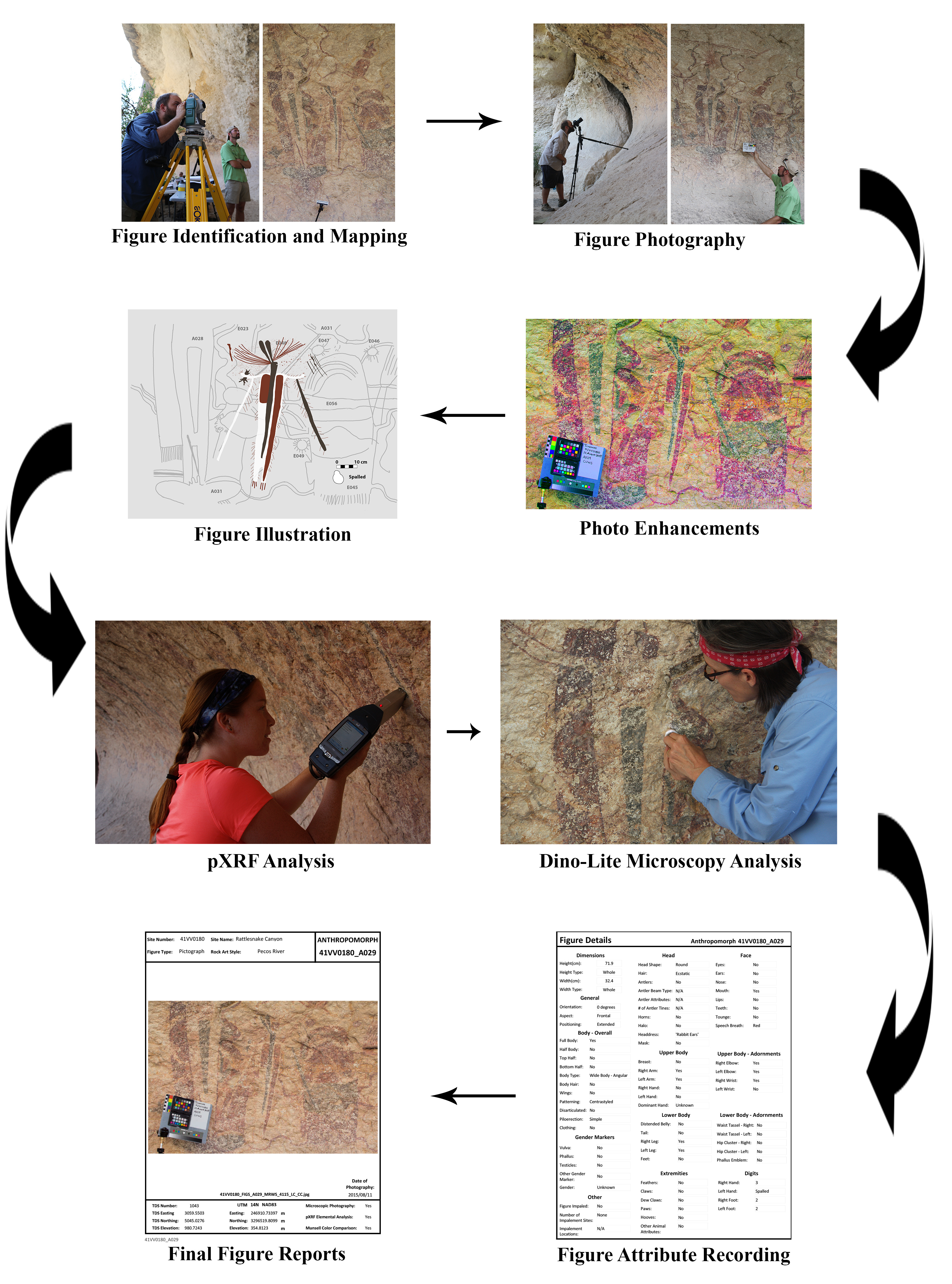

During previous documentation efforts every identified figure would receive photographs, an illustration, copious notes, and meticulous documentation of the iconographic attributes. Depending on the density of the rock art at a site, this process could take weeks, months, or even a couple years. While preparing for the Alexandria Project, we knew that we would need a way to systematically capture the remarkable iconography across the region. After all, we are trying to document every rock art site in Val Verde County! This type of project affords a unique opportunity to create a detailed catalog of iconographic motifs across a large area that will inform countless future studies. However, the amount of iconographic data that can be collected at each site is limited by time constraints.

The Final Inventory

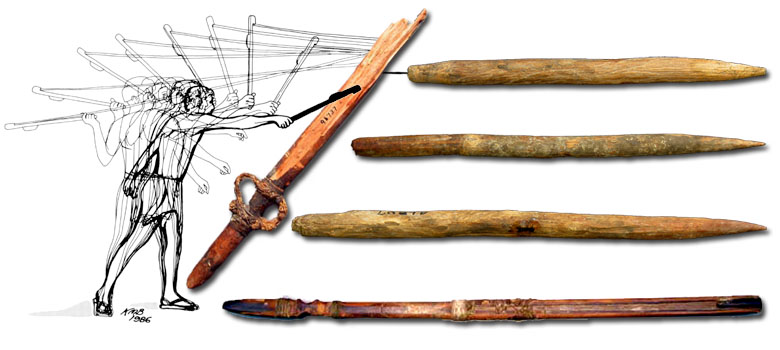

We ended up settling on 36 attributes or symbols that are relatively common throughout Lower Pecos rock art. Some of the attributes we document include the kinds of paraphernalia and adornments present on anthropomorphs (e.g., atlatls, hip clusters, impalements, wings, antlers, etc.), the zoomorphs present (e.g., deer, felines, avians, etc.), and a large series of enigmatic elements (e.g., box with legs, impaled dots, handprints, single pole ladders, etc.). In addition, we also record the presence of 2 complex motifs that are comprised of several specific symbols in association with each other (see Alexandria Project blog post). All of these attributes are entered into our Rock Art Site Form, and are searchable within the Shumla Database.

Future Data Analysis

While the 3D models and GigaPan images (see SfM and Gigapan blog) are extremely important for preserving Lower Pecos rock art for future generations, the iconographic inventory is arguably more important for studying and understanding the rock art. Imagine you are a future researcher, and want to do a study on feline imagery. The iconographic inventory will allow you to search for felines across all known rock art sites in the Lower Pecos. From there you will be able to open the 3D models and GigaPan imagery to launch your analysis. In essence, we are creating a baseline dataset, a stepping stone to go further and beyond.

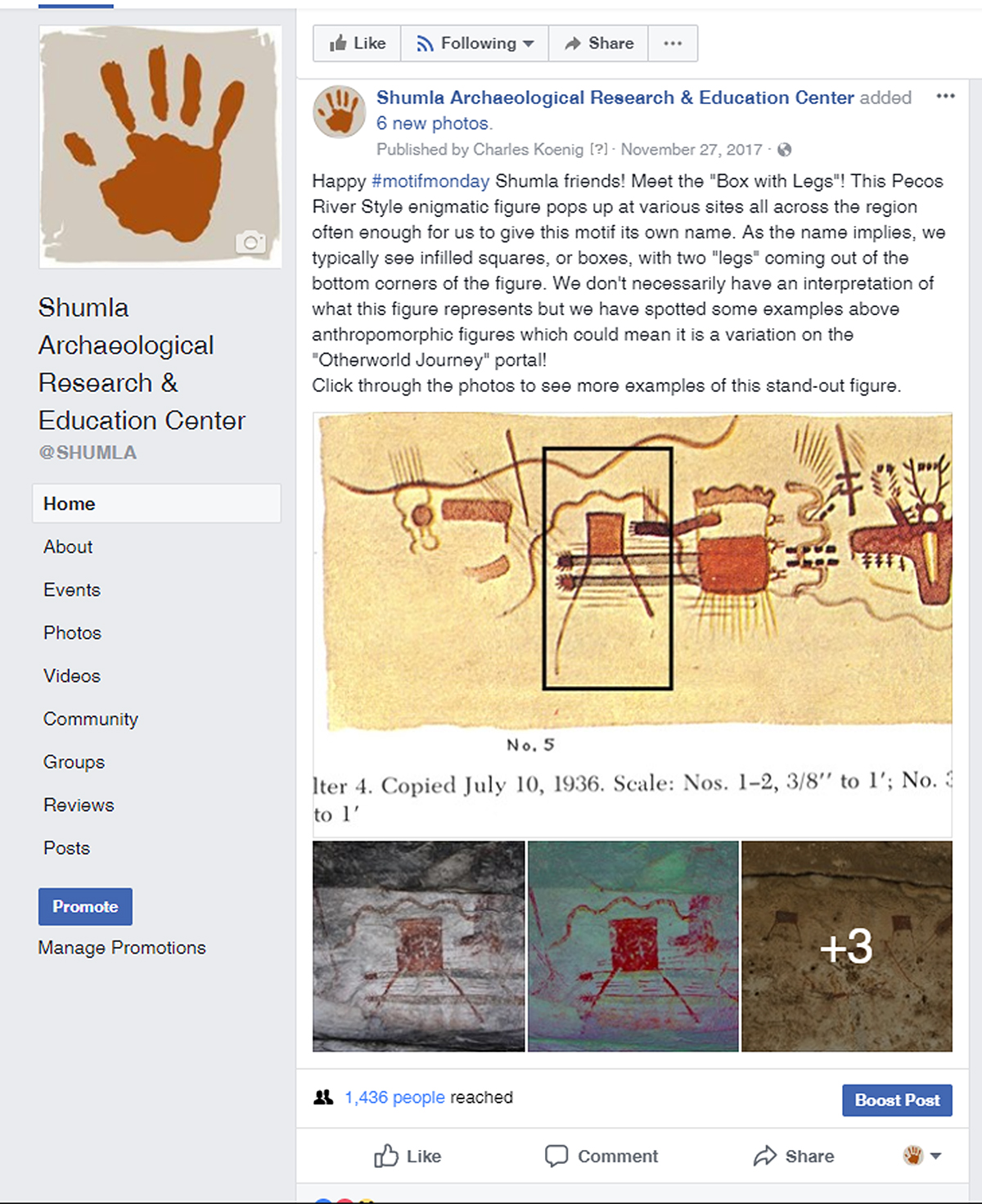

#motifmonday

Throughout the over 50 sites we’ve visited thus far, we are constantly blown away not only by the variety of iconography, but also the diversity of how these symbols and motifs are portrayed. We are already seeing interesting patterns emerge, and we know the iconographic inventory will fuel countless studies in the future. In the meantime, we are slowly sharing small bits of these insights on Facebook with our weekly #Motif Monday posts and through future blog posts.

REFERENCES CITED

Boyd, Carolyn 2016 The White Shaman Mural: An Enduring Creation Narrative in the Rock Art of the Lower Pecos. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Howells, Richard and Joaquim Negreiros 2012 Visual Culture. 2nd ed. Polity. Malden, Cambridge UK.

Hultkrantz, Åke. Panofsky, Erwin 1972 Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance. Originally published 1939. Icon Editions. Westview Press, Oxford.

0 Comments